History Learn more about the history of Grassy Narrows and their struggle to maintain their way of life.

- Before Contact

- Colonization

- Cultural Imperialism

- Environmental Poisoning

- Industrial Clearcut Logging

Before Contact

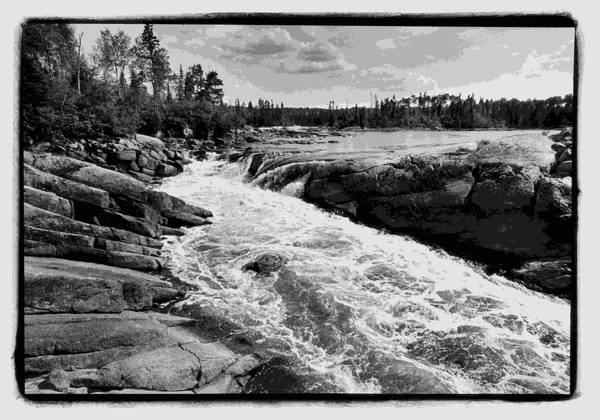

Since time immemorial, the Asusubpeeschoseewagong Anishinabek (Grassy Narrows indigenous people) have lived in the Boreal forest. There was a time not long ago in Grassy Narrows when families were self sufficient and did not know the words “welfare” or “social assistance”. They lived from season to season living off the land and the food it had to offer.

There was summer, a time of picking blueberries, raspberries, strawberries, fishing, drying meat for winter and picking medicines. There was fall, when the trapping and hunting season started, with moose, deer, ducks, partridge, beaver, muskrats as prey. It was also a time for picking wild rice. Winter was rabbit hunting, getting fish through the ice to feed the family, keeping the family warm during the freezing cold days and telling legends and stories during the long dark nights. Spring consisted of tapping the trees for maple syrup and birch syrup, hunting ducks and waiting for the lakes to be free of ice.

Through these traditional activities the community of Grassy Narrows sustained their families and their culture, practiced their spirituality, and supported their economy in a sustainable and self-reliant manner.

Colonization

From the 1850’s onwards, large numbers of European settlers began arriving in the area of Grassy Narrows. On October 3rd, 1873 Treaty 3 was signed which defined the terms by how the land would be shared and how the various cultures would co-exist. The treaty guaranteed Grassy Narrows’ right to continue hunting, fishing and trapping as before. People in Grassy Narrows understood the Treaty to be mean that the plenty of the land would be shared, and that the Indigenous way of life and economy would not be interfered with.

The treaty has never been properly upheld by the government. The Provincial Government has consistently failed to acknowledge that Grassy Narrows has rights over their traditional land. A long succession of decision imposed on Grassy Narrows have attacked their economic base, their social fabric, their culture, and their rights. Today the Ontario Government is grants giant multinational corporations like Weyerhaeuser, the right to log on Grassy Narrows' land without their consent.

The cumulative effects of the Ontario Government's decisions have degraded a once thriving ecosystem, undermined the sustainable local economy, and torn the fabric of a vibrant society.

Cultural Genocide

Throughout much of the 20th Century, as a matter of government policy, the children of Grassy Narrows were forcibly taken from their families to the now infamous Church-run ‘Residential Schools’ that indoctrinated children into the Anglo Saxon way of life. Many suffered abuse at the hands of their caretakers.

In the 1950's hydroelectric damming on the English river, touted by the provincial authorities for their environmental benefits, flooded sacred burial grounds and destroyed wild rice beds – a major food staple. It also drowned out fur bearing animals that were a key source of culturally appropriate income for the community. The consequent deplacement of families further resulted in a loss of traditional knowledge, language, culture and spirituality.

In the 1960s, the community was coerced into relocating from their traditional territory and subsistence life to a reserve near the town of Kenora, Ontario, by the Government. They were told this was the only way they could have a school for their children in their own community. The new reserve was on a small, stagnant lake away from the wide-open rivers the community depended upon for food and water. The new houses within the reserve were laid out in the European style – too close together for Anishinaabe social norms, and many lacked access to the water. The soil was too poor to support kitchen gardens, and houses were assigned without regard to family ties and friendships.

This official program of forced assimilation has taken its toll. Today, many of Grassy Narrows’ youth speak only English, not Anishinaabe, the mother tongue of their parents. The Grassy Narrows Women's Drum group now runs a Cultural Skills Training Program in which community elders and traditional knowledge holders train the youth in the traditional cultural, and survival skills.

Environmental Poisoning

In the 1970’s it was revealed that fish caught by the local fisheries contained dangerous levels of mercury. It was discovered that the source of the mercury was the Dryden paper mill upstream – then ownd by Reed Paper. Today the mill is owned by the New Domtar, a combination of Domtar and Weyerhaeuser's old paper division..

This revelation destroyed a basic food staple – fish – and a corner stone of the local economy. Overnight employment rates in the community went from 90% to 10%. The community was left to deal with the loss of their traditional economy, unemployment and a mysterious new ailment that was rampant among members of their community – mercury poisoning.

Industrial Clearcut Logging

Grassy Narrows' traditional territory is the area where the community has hunted, trapped, gathered berries, wild rice, and medicines, and fished for thousands of years. These forests, lakes, and rivers make it possible for the people of Grassy Narrows to maintain sustainable traditions that have been passed down for generations.

Grassy Narrows' traditional territory is the area where the community has hunted, trapped, gathered berries, wild rice, and medicines, and fished for thousands of years. These forests, lakes, and rivers make it possible for the people of Grassy Narrows to maintain sustainable traditions that have been passed down for generations.

The Ontario Government has granted the rights to log on Grassy Narrows' land to multinational corporations like Weyerhaeuser, without Grassy Narrows' consent. Approximately 50 percent of Grassy Narrows' land has been logged. Weyerhaeuser's contractors use heavy industrialized machinery to clearcut log the endangered forests on Grassy Narrows' land, leaving gaping clearcuts that are sometimes as large as 50,000 acres, 62 times the size of New York's Central Park.

After logging, the scarred land is sprayed with herbicides and then replaced with single species – or monoculture – tree-farms, devoid of the blueberry bushes and plants traditionally used for medicinal purposes. Without healthy forests, much of the wildlife is also disappearing, making it difficult for the Grassy Narrows people to continue hunting and trapping on their traditional land, as well as pick berries that are free from poisonous chemicals.

Around 2002 clearcut logging dramatically accelerated in the area to supply Weyerhaeuser's new Timberstrand / Trus Joist Mill in Kenora, Ontario.